รูปแบบโพรงอากาศของกระดูกสันหลังไดโนเสาร์ซอโรพอดชนิดใหม่ หมวดหินเสาขัว จากแหล่ง ไดโนเสาร์ภูกุ้มข้าว จังหวัดกาฬสินธุ์

Main Article Content

Abstract

Siripat Kaikaew, Suravech Suteethorn and Rut Sonsupap

รับบทความ: 6 กรกฎาคม 2556; ยอมรับตีพิมพ์: 11 ธันวาคม 2556

บทคัดย่อ

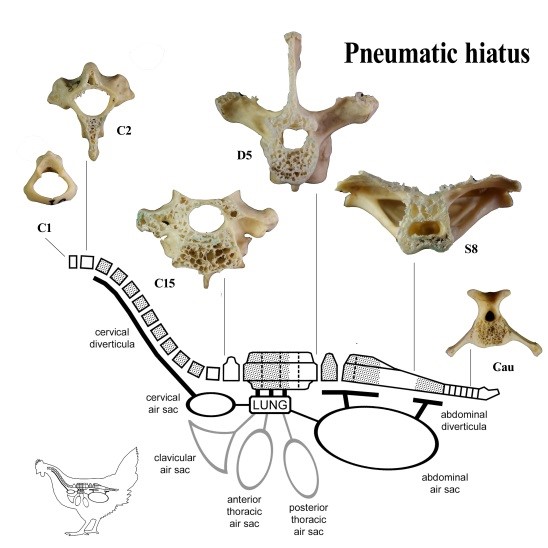

ไดโนเสาร์ซอโรพอดเป็นไดโนเสาร์กินพืชขนาดใหญ่ คอยาว หางยาว และยังเป็นสัตว์บกที่มีขนาดใหญ่ที่สุดในโลก มีการประมาณการว่าซอโรพอดที่ใหญ่ที่สุดอาจมีความยาวถึง 35 เมตร และมีน้ำหนักถึง 100 ตัน ร่องรอยจากฟอสซิลแสดงให้เห็นการออกแบบภายในโครงสร้างของกระดูกไดโนเสาร์เหล่านี้ที่แสนมหัศจรรย์ เพื่อแบกรับภาระน้ำหนักมหาศาลของตัวไดโนเสาร์ และลดน้ำหนักโครงสร้างตัวเอง โดยการพัฒนากระดูกสันหลังที่เป็นโพรงภายใน ดังนั้นจึงเป็นที่มาของวัตถุประสงค์งานวิจัยในครั้งนี้ ในการศึกษารูปแบบโพรงอากาศภายในกระดูกสันหลังของไดโนเสาร์ซอโรพอดชนิดใหม่ที่ค้นพบในประเทศไทย ด้วยการฉายรังสีเอ็กซเรย์ (CT scan) แปลผลเป็นภาพ 3 มิติ และนำมาเปรียบเทียบกับไก่ในปัจจุบัน (Gallus gallus) ได้แก่ ไก่บ้านและไก่ชน พบว่า รูปแบบโพรงอากาศภายในของไดโนเสาร์ชนิดใหม่นี้เป็นแบบโพรงขนาดใหญ่ (large chamber) โดยแกนกระดูกสันหลังส่วนคอ และท้อง ประกอบด้วยโพรงอากาศขนาดใหญ่ ซึ่งต่างจากรูปแบบในกระดูกสันหลังของไก่ที่นำมาเปรียบเทียบ ที่ประกอบด้วยโพรงอากาศขนาดเล็ก (small chamber) กระจายอยู่ทั่วชิ้นกระดูก นอกจากนี้ยังพบว่า ปัจจัยที่แตกต่างในด้านต่าง ๆ เช่น ชนิดพันธุ์ อายุ เพศ และการเจริญเติบโต ไม่มีผลต่อการเปลี่ยนแปลงของรูปแบบโพรงอากาศภายในกระดูกสันหลังของไก่

คำสำคัญ: เทคนิคเอ็กซเรย์คอมพิวเตอร์ โพรงอากาศภายในกระดูกสันหลัง ซอโรพอด Gallus gallus

Abstract

Sauropods were giant, long-necked and long-tailed quadrupedal plant-eating dinosaurs. They were the largest terrestrial animals. It was estimated that the largest sauropod may have reached up to 35 meters long and weighed 100 tonnes. Fossils of these sauropods evidently revealed distinctive structures within their skeletons. These structures included development of air chambers in their vertebrae in order to support their huge body trunks. Therefore, this research aimed to study characteristics of vertebral pneumaticity in a new sauropod dinosaur from the Sao Khua Formation of Thailand. The Sauropod vertebrae were scanned using the computer tomography (CT) technique to examine the internal structures in 3D and compared with those of the extant chickens (Gallus gallus). The vertebrae of the sauropod and chickens were pneumatized. In the sauropod vertebrae the air chambers observed were simple and very large but in the chicken vertebrae they were complex and small. In addition, this study showed that different factors, including varieties, age, gender and growth conditions of the chickens did not have any effects on the structures of the air chambers within their vertebrae.

Keywords: Computed tomography scan, Pneumatic vertebrae, Sauropod dinosaur, Gallus gullus

Downloads

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

References

Buffetaut, E., Suteethorn, V., Cuny, G., Tong, H., Le Loeuff, J., Khansubha, S., and Jongautchari-yakul, S. (2000). The earliest known sauropod dinosaur. Nature 407: 72–74.

Butler R. J., Barrett P. M, and Gower D. J. (2012). Reassessment of the evidence for postcranial skeletal pneumaticity in triassic archosaurs, and the early evolution of the avian respiratory system. PLoS ONE 7(3): e34094.

Butler, R. J., Barrett, P. M., and Gower, D. J. (2009). Postcranial skeletal pneumaticity and air−sacs in the earliest pterosaurs. Biology Letters 5: 557–560.

Hogg, D. A. (1984a). The development of pneumatic-sation in the postcranial skeleton of the domestic fowl. Journal of Anatomy 139: 105–113.

Hogg, D. A. (1984b).The distribution of pneumatisation in the skeleton of the adult domestic fowl. Journal of Anatomy 138: 617–629.

O’Connor, P. M. (2006). Postcranial pneumaticity: an evaluation of soft-tissue influences on the post-cranial skeleton and the reconstruction of pulmonary anatomy in archosaurs. Journal of Morphology 267: 1199–1226.

O’Connor, P. M. (2009) Evolution of archosaurian body plans: skeletal adaptations of an air-sac-based breathing apparatus in birds and other archosaurs. Journal of Experimental Zoology 311: 629–646.

Schwarz, D., and Fritsch, G. (2006). Pneumatic struc-tures in the cervical vertebrae of the Late Ju-rassic Tendaguru sauropods Brachiosaurus brancai and Dicraeosaurus. Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae 99: 65–78.

Sereno, P. C., Wilson, J. A., Witmer, L. M., Whitlock, J. A., Maga, A., Ide, O., and Rowe, T. (2007). Structural extremes in a cretaceous dinosaur. PLoS ONE 2: e1230.

Suteethorn, S., Le Loeuff, J., Buffetaut, E., Suteetkorn, V., Taubmook, C. and Chonglakmani, C. (2009). A new skeleton of Phuwiangosaurus sirindhornae (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from NE Thailand. Geological Society of London Special Publication 315: 189–215.

Wedel, M. J. (2003b) Vertebral pneumaticity, air sacs, and the physiology of sauropod dinosaurs. Paleobiology 29: 243–255.

Wedel, M. J. (2006). Origin of postcranial skeletal pneumaticity in dinosaurs. Integrative Zoology 2: 80–85.

Wedel, M. J. (2003a). The evolution of vertebral pneu-maticity in sauropod dinosaurs. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 23, 344–357.

Wedel, M. J., and Ciffelli, R. I. (2005). Sauroposeidon: Oklahoma’s native giant. Oklahoma Geology Notes 65: 40–57.

Wedel, M. J., Ciffelli, R .I., and Sander, R. K. (2000a). Sauroposeidon proteles, a new sauropod from the early Cretaceous of Oklahoma. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 20: 109–114.

Wedel, M. J., Ciffelli, R. I., and Sander, R. K. (2000b) Osteology, paleobiology, and relationships of the sauropod dinosaur Sauroposeidon. ActaPa Palaeontologica Polonica 45: 343–388.

Wedel, M.J. (2007). What pneumaticity tells us about ‘‘prosauropods,’’ and vice versa. Special Paper in Palaeontololgy 77: 207–222.

Wedel, M.J. (2009). Evidence for bird-like air Sacs in Saurischian dinosaurs. Journal of Experimental Zoology 311A: 611–628.